By Chris Bennett

Despite pressure from some notable economic experts for an increase in the Fed funds rate to combat inflation, the Federal Reserve has held fast to its existing zero interest rate policy, otherwise known as ZIRP. Recent comments from Federal Reserve Vice Chair Richard Clarida reaffirmed the Fed’s previously stated timeline of 2023, and unless economic conditions improve drastically over the next 12 to 18 months, this would be the earliest that the Fed would consider raising the Fed funds rate.

While the Fed’s interest rate policy certainly has an influence on mortgage rates via its effect on the 5-year and 10-year Treasury note rates, there is by no means a one-to-one correlation between the two. Thus, lenders can and should expect continued volatility in mortgage rates through the end of 2021 and into 2022. A quick look at recent historical interest rate trends provides ample evidence of this.

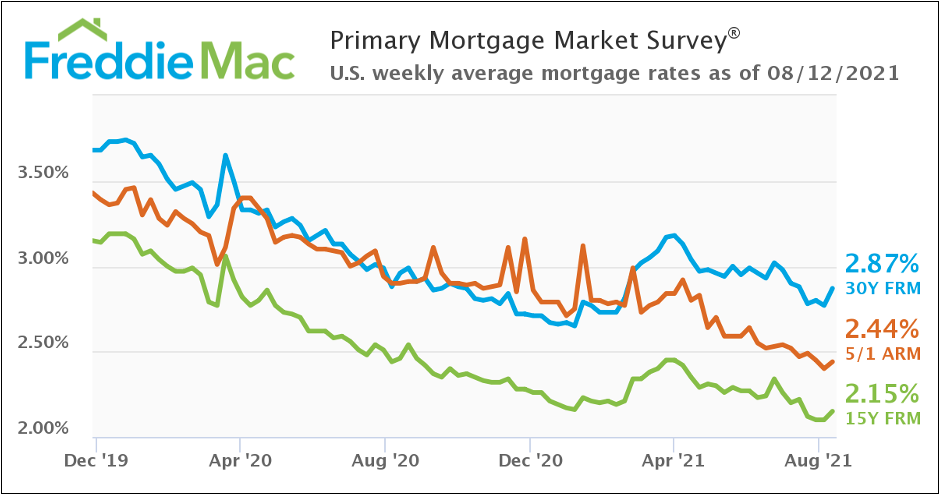

Data from Freddie Mac’s Primary Mortgage Market Survey starting just before the beginning of the pandemic in December 2019 through August 2021 shows numerous peaks and valleys in the average rate for 30-year fixed mortgages despite the general downward trend, with average rates drifting north of 3% several times since the Fed’s rate policy announcement on March 15, 2020.

In fact, the average for a 30-year fixed-rate mortgage jumped 29 basis points in the days following the announcement and didn’t hit sub-3% until mid-July 2020.

While the largest swing so far this year has only been 50 basis points in yields (which occurred in only a six-week span during February and March), history tells us that swings of 400 to even 800 basis points in MBS prices are possible even with the Fed Funds rate locked down near the zero bound. This exact scenario occurred in 2013 during what was known as the taper tantrum.

Although the Fed had instituted ZIRP at the start of the global financial drisis in December 2008, rumblings of a potential liftoff in the Fed Funds rate sent mortgage interest rates soaring by more than 100 basis points, only to see MBS prices reverse and recover by over 6 full points several weeks later — all of which occurred nearly two years before the Fed began increasing the Fed funds rate in December 2015.

On the flip side, events unrelated to the Fed’s activities can also have a tremendous impact on the market. Case in point would be the policy implementation by the GSEs in March 2021 restricting the number of non-owner-occupied and second home mortgages they could purchase, which left many lenders scrambling as prices for these loans dropped as much as 700 basis points.

Eventually, lenders figured out the right strategy for these loans — whether it was to price them accordingly as private-label securities, hold them in portfolio for good yields or continue to sell to or securitize with Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac within the specified limits — and the second home and investment market calmed down to the point where most lenders felt comfortable hedging those as they had previously been.

Of course, now that FHFA has announced that it is suspending the purchase cap, this is all rendered moot going forward.

However, it does underscores the point that ZIRP is no guarantee of market stability, and looking ahead, full FDA approval of COVID-19 vaccines for all ages, the effects of the Delta variant on consumer behavior and changes in macro-economic data or geopolitical events all have the potential to trigger a significant spike or drop in interest rates and bond prices independent of the Fed’s rate policy.

For the 70% of lenders anticipating margin compression in Q3 2021 and beyond, per Fannie Mae’s most recent Mortgage Lender Sentiment Survey, this is not encouraging news as rising interest rates will most certainly curtail the already dwindling refinance market, thus driving down volumes and expected profits. As is often the case, the best defense is a good offense, and for lenders, this means taking advantage of high-volume periods to build a buffer against future margin compression.

In general, lenders are quick to cut their margins when volumes decline but slow to expand them as volumes increase, lest they reverse this uptick in business. Yet, the cyclical nature of the industry practically demands that lenders capitalize on the good times to hedge against the bad, and those that are willing to do so put themselves in a better position to withstand sustained periods of market decline, as well as the brief dips that occur even in the best of times.

As difficult as it can be to predict market movements, one constant lenders can rely upon is that every market upswing is eventually followed by a downturn. The craving for market stability — and the willingness to believe that a change like ZIRP will deliver it — is understandable but misguided. By taking an “eyes wide open” approach to long-term planning vis a vis secondary/capital markets planning and margin management, lenders can better protect themselves against the unexpected.